The first attempts to introduce professional policing to Ireland began in the early 19th Century.

A History of Policing in Ireland

History Timeline

2003

The Royal Ulster Constabulary Memorial Garden was officially opened by HRH The Prince of Wales on 2nd September 2003.

From 1969, many police officers were killed and thousands injured as a result of the security situation. The Royal Ulster Constabulary George Cross Foundation was established by virtue of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000 for the purpose of "marking the sacrifice and honouring the achievements of the Royal Ulster Constabulary" and a memorial Garden was established at Police Headquarters, Belfast, and provides a major tribute to policing in Ireland. It, in particular, marks the service and sacrifice of RUC officers and offers a unique three-dimensional experience unparalleled anywhere in the world.

2001

The Police Service of Northern Ireland is formed.

On 4th November 2001 the RUC transitioned to the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI). The first of the newly recruited PSNI officers commenced their duties in April 2002.

The Police Service currently has around 6,900 police officers and 2,600 police staff and the direction and control of the service is vested in the Chief Constable, who is assisted by a Deputy Chief Constable, Chief Operating Officer and Service Executive Team. The Police Service of Northern Ireland faces the same range of challenges to any other modern police service it is however the only routinely armed service in the United Kingdom with the unique additional challenge of policing in the context of a ‘substantial’ terrorist threat.

For operational purposes Northern Ireland is divided into 3 Areas and 11 Districts to mirror the local council boundaries. Police Service ranks, duties, conditions of service and pay are in line with those of other UK police forces.

2000

Queen Elizabeth II presents the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), with the George Cross.

The Civil Rights Movement of 1968/69 led to serious civil unrest with which the RUC was unprepared to deal due to its small size, limited resources and political control and the army was called in to restore order. A police enquiry followed which radically reformed the RUC to bring it more into line with other UK police forces. The most important changes were the removal of political control over the police by the setting up of the Police Authority for Northern Ireland, the transfer of all military-type duties to the army and the disbandment of the USC and its replacement by a newly recruited RUC Reserve. Another important change was the disarming of the RUC, a situation that had to be reversed after a year due to the escalating terrorist threat.

The escalation of the terrorist campaign in the 1970’s and 80’s saw the RUC develop in both size (to a maximum strength of 13,500) and expertise to meet the challenge. A policy of ‘police primacy’ was adopted from the mid-1970’s, under which the responsibility for security lay in the first instance with the police, with army support available only when necessary.

In addition to countering the terrorist threat the RUC developed specialist units concerned with areas such as serious crime, racketeering, drugs, traffic offences and domestic abuse.

The difficulty and danger of the RUC’s task in the face of years of terrorist violence was recognised by the award of the George Cross to the force in April 2000. A large number of officers also received individual awards for gallantry.

1966

RUC women recruits drilling at the former training depot at Enniskillen, 1966.

Due to the continued problem of political agitation and violence, the RUC had the dual role of combating normal crime and armed subversion from the IRA. It was assisted in the latter role by the Ulster Special Constabulary, which acted as a part-time auxiliary police. Due to its dual role the RUC, like the RIC, continued to be an armed force.

A women’s section was established in 1943 to carry out a limited range of duties, mainly concerned with women and children. The role of female officers expanded after the 1970’s and full equality was achieved in 1994 with the right to carry firearms.

1922

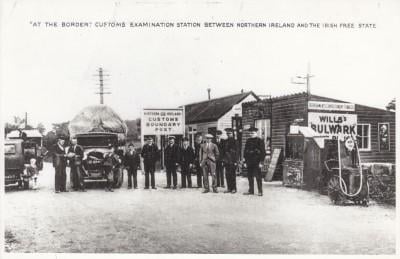

Police and customs officers on duty at the border customs station at Killeen near Newry, c.1922.

By the end of the 19th Century the RIC with an average strength of 11,000 was responsible for the policing of the whole of Ireland with the exception of the city of Dublin which had its own police force, the Dublin Metropolitan Police, (like the RIC controlled by the central administration at Dublin Castle).

Following the partition of Ireland it was decided to disband the RIC as an all-Ireland police force. In southern Ireland a new police force, the Civic Guard later Garda Siochana was formed, while in Northern Ireland the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was established on 1 June 1922 as the police force for Northern Ireland. The RUC carried much over from the former force with a strong nucleus of former RIC men (over 50% of the new force’s 3,000 strength comprised ex-RIC men), the same rank structure, uniform and terms and conditions of service. From 1922 to 1970 control of the RUC was vested in the Minister of Home Affairs, de facto a Unionist politician, a situation which was to create serious difficulties in the perceived impartiality of the RUC in later years.

1892

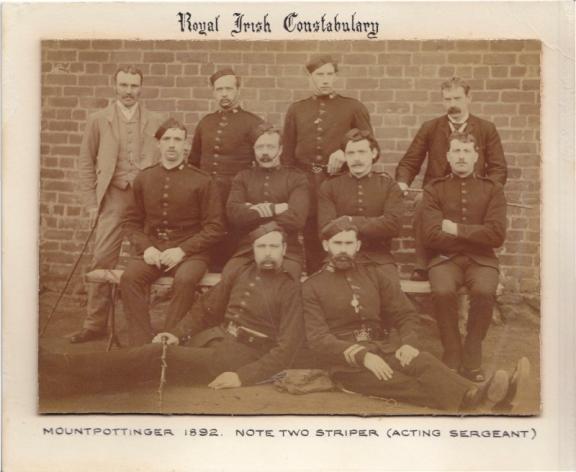

Royal Irish Constabulary at Mountpottinger Barracks in 1892.

Included in the group are two plain-clothed detectives.

The Constabulary of Ireland carried out a full range of policing tasks, but it’s most important task was that of security, due to the ever-present threat of nationalist insurrection. Due to this it was organised as a colonial constabulary and as an armed, quasi-military force, rather than along the lines of other conventional police forces in the British Isles.

In 1867 the constabulary was given a royal title for its part in suppressing the Fenian Uprising of that year and became the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the first royal police force and a model for a number of police forces throughout the world.

1860

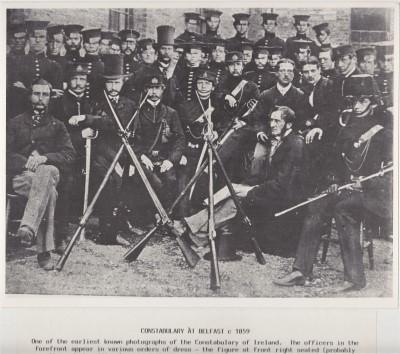

Thought to be taken around 1860, this is one of the earliest known photographs of the Constabulary of Ireland.

It depicts a party of Constables and their officers.

The Constabulary of Ireland was a trained and disciplined force under the central control of the government administration at Dublin Castle. It represented a fresh start in policing and members served under a strict code, which governed all aspects of their lives, on and off duty. Elaborate precautions were taken to ensure that its members displayed strict impartiality at all times. Police Officers who lived in barracks, were prohibited from serving in their (or their wives’) native areas, and were unable to vote or to belong to any political or religious groups (the exception being the Society of Freemasons)

1812

Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel's critical role in the development of policing has been immortalised by the common use of of the names ‘Bobbies’ and ‘Peelers’ for the police.

When appointed to Chief Secretary in Ireland in 1812, Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) found a land in which law and order in many rural areas was breaking down. Local magistrates and the temporary and untrained Baronial Police were unable to deal with a tide of outrages and faction fighting. After attempts to solve the problem by setting up a Peace Preservation Force in 1814 and later a system of county constabularies under the Constabulary Act of 1822, a single police force, The Constabulary of Ireland, was established in 1836.